New course gives students a hands-on learning experience with early filmmaking

Early cinema is not quite ancient history, but it was a long, long time ago.

The short films of the Lumière brothers, for instance, were first publicly screened in December 1895 in Paris. They were black and white, without sound, and quite short – under a minute long.

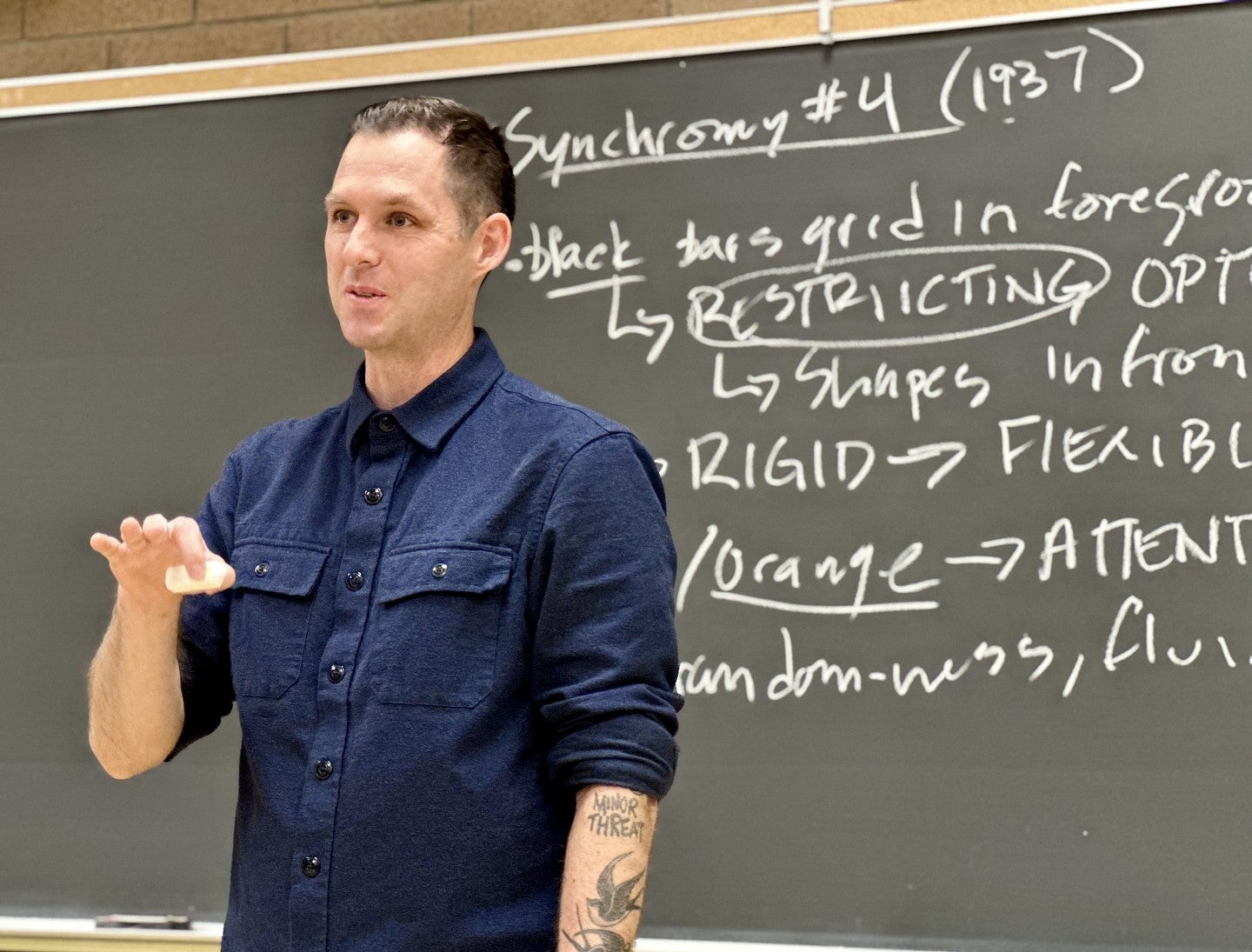

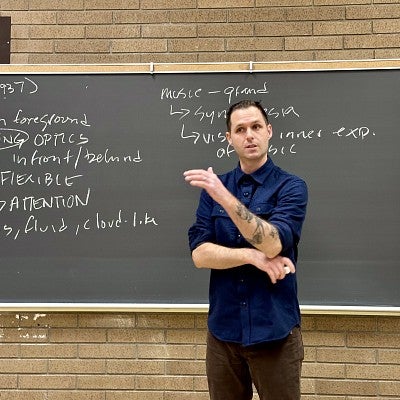

For today’s cinema studies students, those seminal filmmaking efforts can be hard to relate to, especially if students are simply viewing the films and reading about them, as has been the practice, said Colin Williamson, assistant professor of Cinema Studies in the College of Arts and Sciences.

But what if students use the technology and materials available at the turn of the 20th century to make their own films so that it becomes an experiential, hands-on learning experience?

I’m interested in the practice of re-creation as a way of thinking about history. What happens if they can demonstrate a grasp of film history by making a moving image rather than writing a paper?

That’s what Williamson is attempting to do with a new upper-level course on early cinema (CINE 490/590: Hands-On Film History). Boosted by an award from the Williams Fund, Williamson developed the new class, featuring two in-class workshops led by guest artists who will offer hands-on experiences with historically informed animation art.

“I’m interested in the practice of re-creation as a way of thinking about history,” he said. “What happens if they can demonstrate a grasp of film history by making a moving image rather than writing a paper?”

Students “bring a different energy to class when you do that,” he said. “Their curiosity becomes tangible, they become more excited about old stuff.”

His goal is not to turn his students into film historians, but to demonstrate that getting your hands on historical materials changes the way you see the world and your place in it, he said.

Williamson said he regularly checks in with his students about today’s digital culture.

“It’s exciting how much access they have to information, but there’s also this disconnect – they don’t have control over any of it,” he said.

Some students have a strange nostalgia for a material world they never experienced, and that’s why having them create films using historical techniques provides them with a sense of control, he said.

Williamson, who joined the UO faculty in fall 2023, came of age at the height of the digital revolution, with one foot in the pre-digital age and another in the new digital world.

One day when he was an undergraduate, a professor brought in some 16-millimeter film and had the students scan and digitally restore the old celluloid. He thought that was cool and started to fall in love with archival film history.

He eventually earned a doctorate in cinema studies, but that didn’t train him how to be a teacher, he said.

“I benefitted from thinking carefully about teaching and pedagogy and talking more openly with colleagues and peers about what works in classrooms,” he said.

When he started working as a college professor, he used a traditional lecture format but found it wasn’t working for him or his students. So today he uses a more discussion-based or dialogue-driven teaching style. He might deliver a “micro lecture,” then work with the class on questions and responses.

“I felt like that was a better style for me, in following their lead and guiding them, versus a traditional lecture,” he said.

He has found the UO does a good job of encouraging collaboration and providing resources for improving teaching methods, especially in the humanities, which tends to be more solitary than STEM fields, he said.

“Testing out different modes of teaching is really important,” he said.

By Tim Christie, Office of the Provost Communications